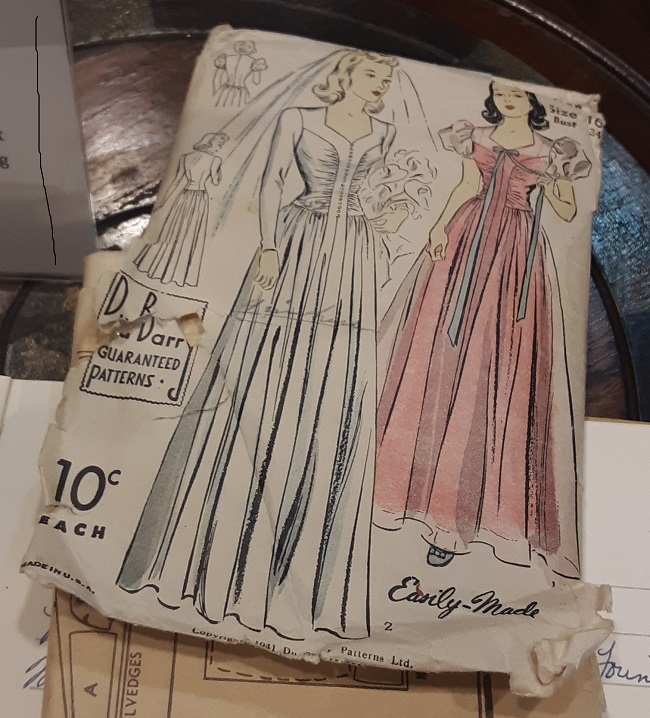

I love a good treasure hunt, and that’s why I head to my local Goodwill bins dig a couple of times a month. And while I always hope to find a clothing treasure, my first stop is always the books bins. Almost every visit turns up at lest one clothing or textile related book. And usually the find is some old out of print book from the past; something I’d probably never know of otherwise.

A recent find was Needlepoint in America by Hope Hanley. A quick look at the photos guaranteed that there would be plenty of information about clothing and accessories, so I bought it and read it. I can remember trying needlepoint in the 1970s during the “colonial” crafts revival craze. By that time most needlepoint came in the form of kits and pre-worked designs. But if you look back to early American needlepoint, you see a freshness and creativity not seen in a kit.

I enjoyed the book because I learned so much. I had heard the term “Berlin work” but until reading this book did not realize it meant the work was made according to a pattern, the first of which where manufactured in Berlin around 1806.

I recently revisited the wonderful Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, or MESDA, in Winston-Salem, NC. I wanted to see needlework, and my husband wanted to see flintlock rifles. We were both pleased with the visit. We did a self-guided tour (more on that later) with the aim of concentrating on items actually made in Salem, NC by the original settlers, Moravians who migrated from their towns in Pennsylvania.

For the interior of North Carolina, the Moravian settlements are quite early, dating to 1753. They were meticulous recordkeepers, so much is known about their lives. From the time Salem was established in 1772, it was a crafts village and marketplace. Workers there were renowned for pottery, silversmithing, and gunsmithing. The arts were acknowledged and encouraged, with there being a town band, and an artist’s studio. Girls were well educated in both academics and needlework. And because the houses and properties tended to remain in Moravian hands, much of their crafts heritage has survived.

And here is where my recent reading of Needlepoint in America came in handy. The dog and cat drawings are a pattern to make needlework slippers, much like the ones seen above. The exhibit notes described the pattern as “Berlin Work Shoe Pattern, P. Trube, Berlin, Germany, 1820-1840. It was exciting to actually see a Berlin work pattern, just like I’d just been reading about! This one is on loan from the collection of Salem College, the school Moravians established for girls.

.

.

This needlepoint pocket book dates to 182o through 1840.

This Berlin work picture is attributed to Moravian Louisa Lauretta Vogler, circa 1835.

It wasn’t all needlepoint. This embroidered linen pocket was made in Salem around 1780. The maker was probably Martha Elizabeth Spach.

This is a little silk sewing bag with a fish-shaped pincushion attached. It was made in Salem circa 1800-1820.

This tiny sewing box has all the original pieces. Unfortunately, the maker is unknown.

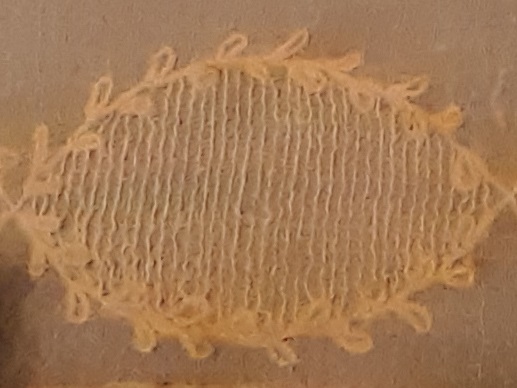

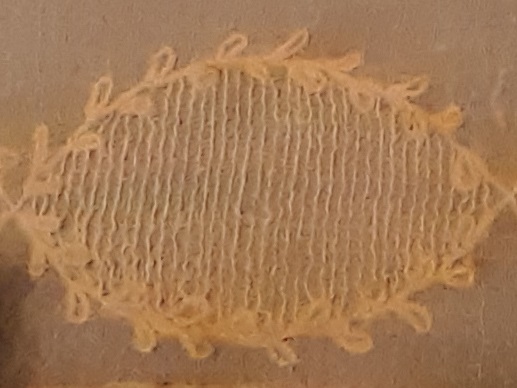

Not all samplers have mottoes and alphabets. Maria Steiner practiced her stitches on this piece of linen in 1808.

Each of the ovals is different.

This creation is a mix of embroidery and painting. Made in Salem between 1825 and 1835, the unknown maker used a variety of materials to construct her picture, including silk thread, chenille, silk fabric scraps, and ribbon.

This rare Southern bandbox came from a Salem milliner’s shop. that of Sarah A. Fulkerson, mid nineteenth century.

This is a needle case, made in Salem in 1838.

Made by tin and silversmith John Vogler, these are silver cape clasps made between 1815 and 1830. Vogler was a prolific craftsman and he lived to be 98.

The early Moravians were pacifists who refused to participate in the Revolutionary War. By the time of the Civil War eighty years later, their stance had softened, with many young men from Salem joining the fight. It appears that many in Salem were against secession, but once the fight started the town provided Confederate soldiers, their brass band, and fabric for Confederate uniforms from a Moravian owned mill.

All this makes the little hand-stitched flag a bit odd. It was made by Emma Miller in Salem in 1865. At the time of the war Moravians as a group were suspected of being Union sympathizers due to their close relationship to the church in Pennsylvania. There’s little evidence supporting the claim, but still, the flag exists.

Here’s Emma with her husband. Maybe she was trying to make something concrete to show her loyalty once it was obvious the war was lost.

The Moravians also had a pottery business, and they made both items that were similar to those of other potters in the region, and pottery that was reminiscent of their Central European heritage. I thought these animal jars were particularly charming.

Salem had a homegrown artist in town, Christian Daniel Welfare. In 1824 he traveled to Philadelphia to study with Thomas Sully, and then returned to Salem the next year, when he painted this self portrait. I loved how the museum put a door frame around the portrait, which seems to invite the viewer into the artist’s studio. Do you think he could have been influenced by Charles Willson Peale’s painting of his sons, which Welfare could have seen in Philadelphia?

Many Salem residents had their portraits painted by Welfare. This is Elizabeth Hege Ruez and her son Zacharias, circa 1825.

And this a a quite sour looking Christina Hege, 1928. She was artist Welfare’s sister-in-law. Note that Christina is dressed in the style of the 1820s.

You can see a marked contrast between the clothing of Elizabeth and Christina and the woman in this portrait, Anna Maria Benzien. This portrait of the Moravian sister was made in London around 1754 before she and her husband went to America. She is wearing the proper dress for a Moravian woman at the time. By 1825 the old rules of dress of the sect were giving way to fashion.

If you are ever in the Winston-Salem area, MESDA should be high on your list of places to visit. Tim and I took the self-guided tour, which gets you into only a small part of the general galleries plus the Moravian galleries. Spend the extra money and take the guided tour, which I have taken in the past. You see so much more.

.

.