The main reason for our recent trip to Cincinnati was to view the current fashion exhibition there, Kimono Refashioned: Japan’s Impact on International Fashion. The second I read that many of the garments in this exhibition were from the collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute, I knew this was an exhibition I simply could not miss.

From the first exhibit (above) to the last, this was a feast for the eye and the mind. At the end of the exhibition the museum had set up ipads for visitors to give feedback. One of the questions was, “Did you learn anything from this exhibition?” I actually saw and learned so much that I had no idea on how to respond.

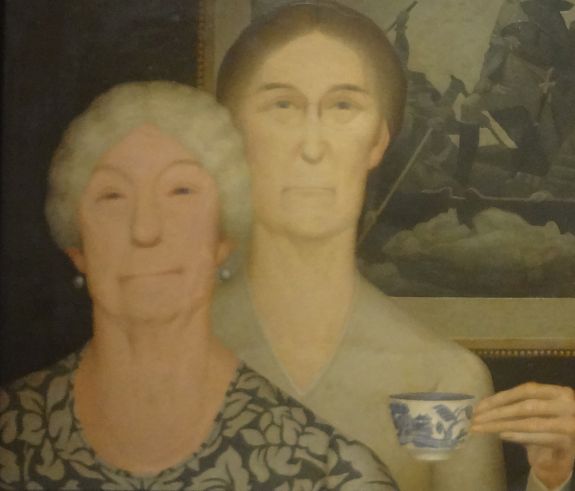

The garment in the foreground was refashioned from a small sleeved kimono called a kosode. The bodice and overskirt were made by court dressers Misses Turner around 1876.

The exhibition included many diagrams to help visitors visualize the concepts presented. Here you get a good picture of how a kimono could be disassembled and cut into pieces to make a fashionable Western dress.

The garment in the background of the top photo is kimono styled in the manner of Western dress with a wide belt instead of an obi. The big difference between the remodeled dress and the original kimono is a matter of shape. In the Western dress the body conforms to the garment; in kimono the garment conforms to the body. In other words kimono is flat, whereas an 1870s dress is three dimensional.

But there’s more to refashioning the idea of kimono than merely cutting one apart to make a Western style dress. In the late nineteenth century Japonism was a very popular area of collecting. Many artists and fashion designers were collectors of Japanese prints and clothing. One collector was the designer of this dress, Jacques Doucet. Dating from the late 1890s, the dress has a typical silhouette of the day, but the applied iris ornamentation was inspired by Japan. There is even a relatively unadored area around the waist, as if the dress might have an obi.

This evening coat from around 1910 more clearly shows the influence of kimono in the loose shape and the motif of the brocade.

This loose fitting evening coat is from Chanel, and was made around 1927. The gold chrysanthemum motif is woven into the silk fabric.

The sleeve cuffs are padded, much in the manner of padded hems commonly seen in kimono.

This dress from Lucile dates to around 1910. The influence of kimono is clearly seen in the wide sash that imitates the obi, the loose fit, the dolman sleeves, and the wrap front.

Sorry about the sorry quality, but I did want to show off the front, if for no other reason than to point out what a great job was done by the exhibition designers in making a plan that allows the visitor to see both the front and the back of the garments. This is so important if one is to get a good understanding of how a garment works.

The back of an evening coat from the House of Worth…

and the front, circa 1910. The wrap front and the dip in the back of the neck are both borrowed from kimono.

And here is the front of this amazing coat from French couturier Georges Doeuillet.

Motif and shape tell us this circa 1913 coat from Amy Linker was heavily influenced by kimono. In fact, this style coat was referred to as a manteau Japonaise in French fashion publications.

Scattered throughout the exhibition were actual kimono, like this early twentieth century example.

The evening coat is attributed to Liberty & Company, and the dress beneath is a Fortuny Delphos gown. The ideas adapted from kimono went perfectly with other garments associated with the dress reform movement.

Does it get any better than this?

This dress is a 1920s Paul Poiret. It is a one-piece dress that was constructed to look like a haori worn over a kimono, with the sash serving as an obi.

This Vionnet dress brings us back to the idea of flat garments. The 1924 dress uses an adapted T motif, which is patched together from pieces of gold and silver lamé.

Also from Vionnet is this wedding dress from 1922. It’s not quite as obvious, but this dress is also made almost entirely from square and rectangular pieces.

Another great feature of this exhibition was the use of paintings that showed the influence of Japonism on Western culture. This 1890 work, Girl in a Japanese Costume is by American artist William Merritt Chase and was on loan from the Brooklyn Museum.

And I’ll end this tour with a look at another kimono from Cincinnati Art Museum’s collection. The exhibition pointed out that the origins of the kimono have been traced back to the Han Dynasty in China. So you see, borrowing good ideas from other cultures is nothing new. I’ll revisit this idea next week.

I am only covering one half of the exhibition because photos were not allowed in the second half which featured more modern garments. I will just say that the more I see the work of Issey Miyake and Rei Kawakubo, the more I understand and love it.

Most of the garments were from the Kyoto collection, with other coming from Cincinnati. The show was a collaboration between those two museums, the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, and the Newark Museum. It will be on display through September 15. I highly recommend it.