I’m fascinated with quilts. No, I don’t collect them, nor do I make them. It’s the historical meaning hidden within these little pieces of textiles that keep me interested in them.

Recently I drove to the Pickens flea market in Pickens, SC. I’d been before, and knew that it’s a very mixed bag of good and bad, new and old, and down right bizarre. The highlight of the visit was a bluegrass band in which a little mutty dog was the fifth member. He had been taught to let out a howl at just the right time. I was too amazed to even take a video.

I had been all over the field – and it’s a big one – with no luck when I stumbled upon a used book seller. He had a few books on quilting so I stopped to have a browse. I asked the price, which was a dollar each, so I was feeling extravagant and had about five or six picked out when the seller said he had more in the back of the truck.

What he had was the entire library of a long-time quilter. There were easily several hundred books on quilts, most of them how-to books. I wasn’t interested in those, but there were also quite a few books on quilt and textile history. I ended up with eighteen of them, which he let me have for $10.

The prize of the lot is the book above, Barbara Brackman’s quilting classic, Clues in the Calico. I had been looking for this book for a long time, but I didn’t want to pay the high price it commands. It is a guide to dating quilts, but more than that, it’s a guide to identifying antique textiles. I’m still reading this one, but I found myself using the information a few days ago when someone on Instagram posted a recently found hoard of old fabrics. Immediately I knew that some of the prints had been printed with “fugitive” green dyes, as the stems and leaves of plants were now a tannish brown.

Some of the books are general quilt histories, but most focus on a particular type or region. I thought this title was very interesting, as I do not associate quilting with Native Americans. I’ll probably put this one at the top of the reading queue.

There were also a couple of books on textiles, and in particular the types of textiles commonly used for quilts.

I’ve read probably four or five of the books, and I’m beginning to see quite a bit of the same information. That’s not a bad thing. I certainly don’t want to read conflicting “facts” as then, how would I figure out who to trust?

Several of the authors have pointed out one of the big fallacies of early quilt-making in America: that colonists made patchwork quilts out of their old textiles out of necessity. I already knew this, but it seems to be a generally held belief when so many writers take the time to make sure that the earliest quilts were not scrap projects in a make do and reuse sense. The earliest American quilts were generally whole cloth quilts, or were quilts made from appliques cut from fabrics that were printed specifically for that purpose.

Two of the books are detailed accounts of the quilts of one family of makers. I’m in the process of reading one of these, Mary Black’s Family Quilts, by Laurel Horton. I’m enjoying this one partially because Mary Black lived in Spartanburg, SC, which is only an hour and a half down the road from me. And besides that, many quilt books tend to focus on quilts from Pennsylvania or New England, so it’s nice reading about quilts from a Southern family.

I need to point out that it’s almost impossible to separate the production of quilts, textiles and clothing in the days before the Industrial Revolution. All the quilt books I’ve read so far also discuss cloth and clothing production. I’ve had to stop and remind myself that the authors of these books are quilt – not clothing – experts.

In referring to the South Carolina backcountry in the late 18th century, Horton writes, “Fabrics were available in abundant variety in local stores for home sewing as was ready-made clothing.” While ready-made fabrics were readily available, ready-made clothing was not. Most of the ready-made clothing at this time was very cheaply made, and was marketed in the South as being appropriate for enslaved people. The best explanation I know of for this is found in Suiting Everyone: The Democratization of Clothing in America by Claudia Kidwell and Margaret Christman.

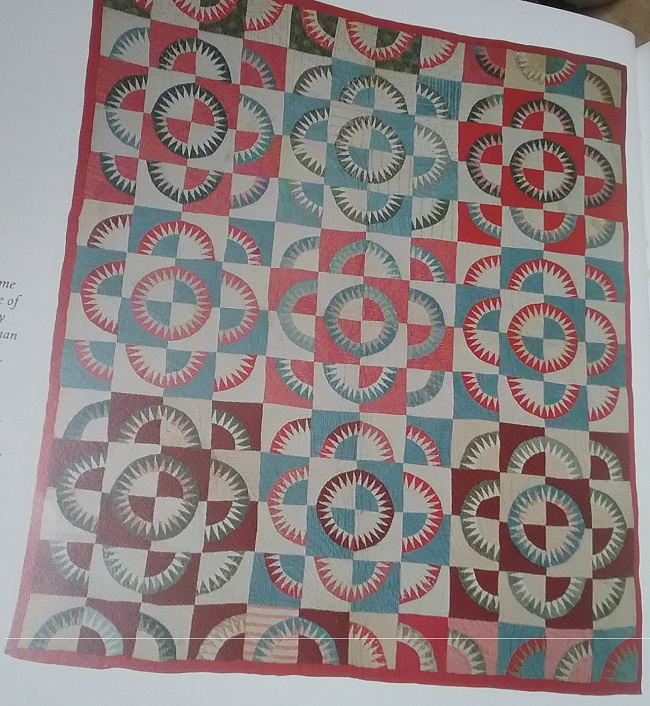

Okay, no more quibbling over the details; let’s look at some quilts. The one above is pictured in Kentucky Quilts 1800 – 1900 by John Finley and Jonathan Holstein. It was made by Ann Johnson Armstrong, circa 1890.

Emma Van Fleet made this quilt in 1866 to commemorate the Civil War battles in which her husband had fought. There are forty-seven battles. Seen in Threads of Time by Nancy J. Martin.

The maker of this one, also seen in Threads of Time, is unknown. It was made around 1865.

And finally, this marvelous creation is seen in New Discoveries in American Quilts by Robert Bishop. The quilt was made by Celestine Bacheller, and the blocks are thought to depict real places around her home in Massachusetts.

It’s a sort of scenic/crazy quilt hybrid. It is now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.